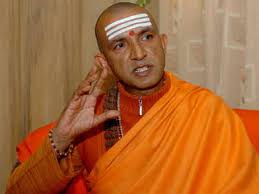

Swami Niranjanananda Saraswati

Sage Patanjali speaks of asana as sthiram sukham asanam. Does it mean that asana is that in which one is sthira and sukhi, or does it mean that sthirata and sukha are outcomes of practising asana?

Sthiram and sukham, stability and comfort, are the outcome of asana practice. Once they are the outcome of the asana practice, the posture itself becomes steady.

Who can sit for five minutes without moving? Stillness does not come naturally, for stillness is not the nature of the senses. The entire body is governed by the senses. Distractions in the body are caused by the senses. Distractions and disturbances in the mind are caused by the senses. When you practise asana, you are not practising a physical posture. The body takes on a physical posture, however the effect of it is to reduce the hyperactivity of the senses. Once the hyperactivity of the senses is reduced, the body enters into a state of comfort and ease. Then a posture can be maintained for a longer period.

Patanjali is advocating only those asanas which are static and comfortable. His first sutra is: Atha yogah anushasanam – ‘Now, instructions on raja yoga’. This is interpreted by many people as meaning that raja yoga is a continuation of a previous yoga, and that previous yoga is hatha yoga.

By the time you come to raja yoga, you have done all the physical movements that you need to do. Therefore, the focus of raja yoga is not on the practice of asana, but on the maintenance of the physical posture.

Even if you do vrischikasana, sirshasana, mayurasana, or surya namaskara, in a manner in which you are experiencing steadiness and comfort in all the different movements and postures, you will be fulfilling the criteria of Sage Patanjali.

The stillness of body and mind in a posture will lead you to pratyahara, introversion. Although stillness and comfort are the outcome of the asana practice, you have to remember that the statement is being made in relation to the stillness leading to pratyahara.

What is pratyahara? Is it withdrawal of senses from external objects, withdrawal of the mind from the senses, or withdrawal of the thoughts?

Pratyahara is an interesting topic. The purpose of asana is to silence the hyperactivity and the agitations of the senses and the mind, leading to the experience of pratyahara. There are three ways I have defined pratyahara and there are three progressive stages of pratyahara.

The turtle

Sri Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita tells Arjuna to withdraw the senses and the mind, just as a turtle withdraws the arms, legs, tail and head into its shell. Therefore, according to the Bhagavad Gita, withdrawing from everything and being self-contained is pratyahara.

Now, what does one withdraw? The senses and the mind. There are five physical senses, the karmendriyas, the organs of action; and there are five organs of knowledge, jnanendriyas; which are the physical senses. And there is the mind, the sixth sense, the sixth sensory organ.

Pratyaya, the old file

There is a word in Sanskrit pratyaya which means an image created in the mind. For example, a guest or student comes and stays one month at Ganga Darshan. You relate and interact. Then the person goes back home, yet in your mind, you have the pratyaya, the image. Whenever a letter comes, whenever an email comes, the same pratyaya will set in, and the same information will come forward. It is like pulling the old file to know who that person is. That is pratyaya.

Pratyaya indicates a connection, an awareness in you about someone or something. This can happen with any object, even a stone can become a pratyaya. If you are walking on the street and you trip on a stone, the stone will become a pratyaya. If you are seeing a nice flower, that flower will become a pratyaya. If you see on your early morning walk, two dogs fight, that image will become a pratyaya. Anything that one receives through the senses becomes a pratyaya, an impression.

Pratyahara is to rid oneself of these impressions for these pratyayas also cause opinions. This person is nice, this person is not nice. This person is good, this person is bad. This person is helpful, this person is gentle. This person is loving, this person is cantankerous. This opinion, based on pratyaya, is the cause of the disturbance in your mind during meditation. That has to be eliminated.

Prati-ahara, feeding oneself

We are continuously receiving inputs from all sources and all directions. That is ahara, feeding oneself. How many sounds are you hearing? An incredible number of sounds, however the brain is filtering only those which are relevant at present. Prati-ahara, everything is coming in. You may only be aware of a partial fragment of the whole experience, yet everything is taken in.

Is it possible to reverse that? Instead of it coming in, can you put it out and empty yourself of it? This emptying oneself is knows as karma kshaya, or the reduction of samskaras, or overcoming the karmas. Therefore, the three stages of pratyahara are:

- Withdrawal – to stop the agitations of the senses.

- Observation – to disconnect from the pratyayas, the impressions, which are cluttering the mind.

- Emptying – to throw out all the rubbish from the mind.

These three stages indicate the sequence in pratyahara.

Whatever practice you do, whether it is thought or emotion observation, mantra repetition or breath awareness, it is only a step to move into the stages of pratyahara in a more controlled manner.

How can we do our duties in the best possible way, yet avoid projection of our egos?

The English word is ego, but the Sanskrit word is ahamkara. How to deal with this ego, this ahamkara? It is distracting, disturbing and hard to manage.

Ahamkara is not ego. It is composed of two words. Aham means I, akara means form, shape or identity. Therefore, the word ahamkara means my identity, my nature, my personality. What I am, the whole thing, is ahamkara, the self-awareness, the self-identity. Self-image, self-prestige, self-esteem become part of self-recognition, ahamkara.

This is good, as long as you are content. When this ahamkara, this pure self-awareness, comes in contact with external sense objects, it does not remain ahamkara. It transforms into something else. The self-identity or self-awareness when in relation with sense objects takes the form of abhimaan, arrogance, and ghamand, pride.

Pride and arrogance, ghamand and abhimaan, together, are known as ego in English. Ahamkara is not known as ego. The statement, “He is very egotistical” is always negative. “He has a big ego” is always in a negative context. Therefore, you have to deal with your pride and arrogance, not with your self-identity, your ahamkara. You have to deal with your ego, which is the combination of pride and arrogance, ghamand and abhimaan. This can only happen through self-observation, and reminding yourself continuously and constantly what you have to do.

You train an untrained animal, a dog, horse, bird, any animal by repeating the instruction over and over again. You have to be more alert and aware than the animal to actually control and instruct the animal. If you are not alert, you will not be able to teach anything to the animal. You have to keep on repeating, “Sit, sit, sit, sit, sit,” every time the animal moves. Are you able to do that to yourself? If you are not, start from the beginning again.

That is the level of competence one has to acquire to succeed in yoga. For that, the drashta identity, the sakshi identity, the witness identity is important. You have to be able to witness, rather than be caught and swept in the stream and flow. You have to become the witness of yourself. Therefore, continuously remind yourself, “No, not this, not this, not this, not this.”

Anything which triggers a negative response has to be eliminated. “Oh no, that person is again going to bug me.” Instantly, that thought has to be disposed of for it will fuel your pride and arrogance, and you will be caught more in your ego-eccentric behaviours, than in your ego-free behaviour.

This is where most people fail as they cannot differentiate between ego-centric behaviour and ego-less behaviour. No matter how great or how elevated a sadhaka might be, when he has to give up ego-centric behaviour and express ego-less behaviour, he fails. That is the test of a sadhaka.

6 March 2016, Ganga Darshan, Munger